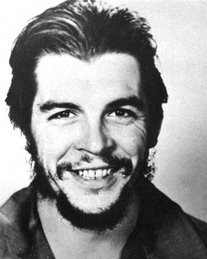

Aquí se habla de uno de los primeros premios Nóbel de la Paz cuyo ejemplo

encandiló a dos jóvenes argentinos. Como estudiaban y practicaban la

medicina admiraban a Schweitzer y anhelaban abrir un hospital para pobres

en América siguiendo su ejemplo. Comenzaron con los leprosos y luego con

los pobres, los movía un enorme amor por los seres humanos y llegaron uno

a fundar la Escuela de Medicina en Santiago de Cuba y el otro a imbricarse

en la memoria colectiva de la Humanidad.

Doctores Alberto Granado y Ernesto Che Guevara, Albert Schweitzer estaría

muy orgulloso de ustedes.

Eladio González - toto

Por favor circule ampliamente este artículo. ¡Gracias!

¿Quién cuida al cuidador? 2012-05-04

Las primeras y más antiguas cuidadoras han sido nuestras madres y abuelas

que desde el principio de la humanidad han cuidado de su prole. Si no hubiera

sido por ellas, ninguno de nosotros estaría aquí para hablar de cuidado.

En este contexto queremos mencionar dos figuras, verdaderos arquetipos del

cuidado: el médico suizo Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965) y la enfermera inglesa Florence Nightingale (1820-1910).

Albert Schweitzer era un eximio exegeta bíblico y uno de los mayores concertistas de Bach de su tiempo. A los treinta años, famoso ya en toda Europa, dejó todo, estudió medicina para, en el espíritu de las bienaventuranzas de Jesús, cuidar de los más pobres de los pobres (los leprosos) en Lambarene (Gabón). En una de sus cartas confiesa explícitamente: «lo que necesitamos no son misioneros que quieran convertir a los africanos, sino personas dispuestas a hacer lo que debe ser hecho a los pobres, si es que el Sermón de la Montaña y las palabras de Jesús tienen algún valor. Mi vida no está ni en el arte ni en la ciencia sino en ser un simple ser humano que en el espíritu de Jesús have algo por insignificante que sea». Fue uno de los primeros en ganar el premio Nobel de la Paz.

Vivió y trabajó durante cerca de cuarenta años en un hospital construido por él con el dinero de sus giras dando conciertos de Bach. En sus escasas horas libres tuvo tiempo para escribir una vasta obra centrada en la ética del cuidado y del respeto por la vida. Expresó así su lema: «la ética es la responsabilidad ilimitada por todo lo que existe y vive». En otra obra afirma: «la idea clave del bien consiste en conservar la vida, desarrollarla y elevarla a su más alto valor; el mal consiste en destruir la vida, perjudicarla e impedir que se desarrolle plenamente; este es el principio necesario, universal y absoluto de la ética».

Otro arquetipo del cuidado fue la enfermera inglesa Florence Nightingale. Humanista y profundamente religiosa, decidió mejorar los modelos de enfermería de su país.

En 1854 con otras 28 compañeras Florence se trasladó al campo de guerra de Crimea, en Turquía, donde se utilizaban bombas de fragmentación que causaban muchos heridos. Aplicando estrictamente en el hospital militar la práctica del cuidado redujo la mortalidad del 42% al 2% en 6 meses. Este éxito le dio notoriedad universal.

De vuelta a su país y más tarde en Estados Unidos creó una red hospitalaria que aplicaba el cuidado como eje orientador de la enfermería y como su ética natural. Florence Nightingale continúa siendo una referencia inspiradora.

El agente de salud es por esencia un curador. Cuida de los otros como misión y como opción de vida. Pero ¿quién cuida al cuidador?, título de un hermoso libro del médico Eugênio Paes Campos (Vozes 2005).

Partimos del hecho de que el ser humano es, por su naturaleza y esencia, un ser de cuidado. Se siente predispuesto a cuidar de los otros y siente la necesidad de ser cuidado él también. Cuidar y ser cuidado son elementos existenciales (estructuras permanentes) indisociables. Es sabido que cuidar es muy exigente y puede llevar al cuidador al estrés. Especialmente si el cuidado constituye, como debe ser, no un acto esporádico sino una actitud permanente y consciente. Somos limitados, sujetos al cansancio y a la vivencia de pequeños fracasos y decepciones. Nos sentimos solos. Necesitamos ser cuidados, si no, nuestro deseo de cuidar disminuye. ¿Qué hacer entonces?

Lógicamente, cada persona tiene que afrontar con sentido de resiliencia (capacidad de remontar) esta situación dolorosa. Pero este esfuerzo no sustituye el deseo de ser cuidado. Es entonces cuando la comunidad del cuidado, los demás trabajadores de la salud, los médicos y el cuerpo de enfermería tienen que entrar en acción.

También el enfermero o la enfermera, el médico y la médica sienten necesidad de ser cuidados. Necesitan sentirse acogidos y revitalizados exactamente como las madres hacen con sus hijos e hijas. Otras veces sienten necesidad de cuidado como soporte, sostén y protección, cosa que el padre proporciona a sus hijos e hijas.

Entonces se crea lo que el pediatra D. W. Winnicott llamaba holding, es decir, aquel conjunto de cuidados y factores de animación que refuerzan el estímulo para seguir cuidando a sus pacientes. Cuando reina este espíritu de cuidado, surgen relaciones horizontales de confianza y de mutua cooperación, y se supera el malestar, nacido de la necesidad de ser cuidado.

Feliz el hospital y más felices aún los pacientes que pueden contar con un grupo de cuidadores. No tendrá «prescribidores» de recetas ni aplicadores de fórmulas sino «cuidadores» de vidas enfermas que buscan la salud. La buena energía que irradia el cuidado refuerza la curación.

Please circulate this article widely. Thanks!

Who Cares for The Caregiver?

Leonardo Boff

Theologian

Earthcharter Commission

The first and most ancient of caregivers were our mothers and grandmothers, who from early humanity have cared for the children. But for them, none of us would be here to talk about caring.

We would like to mention in this context two figures, true archetypes of caring: the Swiss physician, Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965) and the British nurse, Florence Nightingale (1820-1910).

Albert Schweitzer was an exceptional Biblical exegete and one of the best concert interpreters of Bach of his time. When he was 30 years old, already famous throughout Europe, he left everything, and studied medicine, in the spirit of the beatitudes of Jesus, to care for the poorest of the poor, the lepers, in Lambarene (Gabon). He explicitly confessed in one of his letters: «what we need are not missionaries who want to convert the Africans, but persons ready to do what must be done for the poor, if the Sermon on the Mount and the words of Jesus are to have any value. My life is neither in the arts nor in science but in being a simple human being who, in the spirit of Jesus, does something, no matter how insignificant it may be». He was one of the first Nobel Peace prize laureates.

Schweitzer lived and worked for about forty years in a hospital he built with money earned from his Bach concert tours. In his scarce free hours, he managed to write a vast work centered on the ethics of caring and respect for life. He expressed his motto this way: «ethics is the unlimited responsibility for all that exists and lives». He affirms in another book: «the key idea of good consists of preserving life, developing and raising it to its highest value; evil consists of destroying life, damaging and precluding its full development; this is the necessary, universal and absolute principle of ethics».

Another archetype of caring was the British nurse, Florence Nightingale. A humanist, and profoundly religious, she decided to improve the nursing models in her country.

In 1854, with 28 companions, Florence went to the Crimean war, in Turkey, where fragmentation bombs that caused many casualties were being used. Strict application of the practice of caring in the military hospital reduced mortality from 42% to 2% in 6 months. This success brought her universal notoriety.

Back in her country, and shortly thereafter in the United States, she created a network of hospitals that applied caring as the fundamental principle guiding nursing, and as its natural ethic. Florence Nightingale continues to be an inspiring reference.

Health workers are fundamentally caregivers. They care for the well being of the others, as a mission and a life option. But, who cares for the caregiver? ¿Quem Cuida do Cuidador? is the title of a beautiful book by physician Eugenio Paes Campos (Vozes 2005).

We start from the fact that the human being is, by nature and essence, a being of caring. The human being feels predisposed to care for the other, and also feels the need to be cared for. To care for and to be taken care of are existential elements (permanent structures) that are inseparable. It is known that caring is demanding, and can cause stress to the caregiver. Specially if the caring constitutes, as it should be, not a sporadic act, but a permanent and conscious attitude. We are limited, subject to becoming tired, and to experiencing small failures and deceptions. We feel alone. We need to be cared for, if not, our desire to care for others diminishes. What must we do then?

Logically, each person must confront with resilience (the capacity to heal) this painful situation. But this effort is no substitute for the desire to be cared for. It is then that the community of caregivers, other health workers, physicians and the body of nurses, must take action.

Nurses and physicians, male and female, also need to be cared for. They need to feel welcomed and revived, exactly as mothers do with their sons and daughters. At times they feel the need for caring as support, sustenance and protection, things that a father offers to his sons and daughters.

That is when what pediatrician D. W. Winnicott called holding is created: namely, the group of caring and animating factors that strengthen the stimulus to continue caring for the patients. When this spirit of caring prevails, lateral relationships of trust and mutual cooperation appear, and the discomfort born of the need to be cared for is overcome.

Happy is the hospital and still happier are the patients who can count on a team of caregivers. They will have neither «signers of medical prescriptions» nor providers of formulas, but human beings «caring» for infirm lives that seek health. The good energy that caring irradiates reinforces healing.