Chesucristo: Christ and Che, fusions, myths and realities David Kunzle, UCLA

Chesucristo: Christ and Che, fusions, myths and realities David Kunzle, UCLA

Version Feb 15, 2006 . Revised Jan 24, 2007

1 and 2 enclosed

3. Biography David Kunzle, Distinguished Professor of Art History, UCLA, includes among his many articles and books Che Guevara, Icon Myth and Message (1997), and The Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua 1979-92 (1995).

4. to come

5. Keywords Jesus Christ, Cuba, Ernesto Che Guevara, Korda photograph, Bolivia, Christian symbols, The Passion, Anglican.

6. Abstract: Cuba, and a few “heretical” interpreters of scripture have seen Jesus in the context of armed struggle against the Roman occupiers. With the Gospels, Jesus became largely disarmed. In the generation since Che’s death, Che Guevara has become disarmed, that is, associated with the struggle for social justice, and peace, rather than with revolutionary violence and the gun. The world-famous Korda photograph particularly has lent itself to this pacification, for its expression of a serene visionary. Meanwhile, many of the attributes of Jesus and events from his Passion were fused into the iconic Che images: three letter name (IHS=CHE), star, halo, stigmata, crown of thorns, crucifixion, Deposition/Pietà etc. The Anglican church did the reverse: fused a Jesus face into that of Che. Is the Left trying to recover a Jesus stolen by the Right?

7. Contact: David Kunzle, O: 310 825 8232, H: 310 474 6774, Dept of Art History, UCLA. Los Angeles Ca. 90095-1417, Kunzle@humnet.ucla.edu

Text

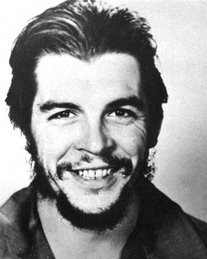

Ever since Christianity became a state religion, and a religion acceptable to the secular power, which is the great bulk of its history, it has presented itself as pacific, even pacifist, a revolution of the spirit, a promise of future life, and not of bodily existence, nor of the present, nor actual material social conditions. Christianity has made its peace again and again with even the most beilligerent of secular powers, with imperial powers, with ruling tyrants and the rich. “Render unto Caesar…” has been the watchword. It is hard to see this as consonant with Jesus’ “option for the poor,” nor with the evidence of continuous popular revolt against the Roman rule in 1st century Palestine. It is in the context of Jesus’ “option for the poor,” enshrined in and since the Sixties in the Theology of Liberation, as well the minority view that very early Christianity, and indeed Jesus’ own life, was very probably not entirely pacific, that we find the conjunction of Jesus with a famous contemporary apostle of armed revolution: that Chesucristo, as I first named the fusion in an exhibition devoted to the imagery of Che Guevara. To be sure, very few theologians or clergy today dare to accept the historical probability that Jesus, apart from being obviously a great spiritual leader, if not himself armed (leaders often do not need to be), was leader of, or at least associated with, one of the many armed struggles of the period against the Roman occupation. (FIG 1 about here)

If we can see Jesus in this way, Could a contrary but converging historical revision also be taking over the myth of Che Guevara? Che over the past generation since his death, Jesus over the generation or two since his death (by the time the gospels were written), and of course over the millennia since then, became disarmed. This is not the place to rehearse the arguments, or even to point to places in the gospels, where, residually, the idea of armed resistance in Jesus and among his followers survives the early ideological purifications. To compare Che’s taking of Santa Clara with a Christ-associated attempted takeover of the Temple (coded in the gospel discreetly as “driving out the moneychangers”) will no doubt seem absurd, if not blasphemous. But Cuban artist Rostgaard’s controversial Christ armed (FIG 2) intuits a long-hidden historical probability.

Twentieth century Latin America and indeed much of the Third World may aptly be compared with first century Palestine. Latin America today has been dubbed “the Galilee of our time” by Cardinal Sebastiano Baggio, under the new Roman empire, U.S.-led international capitalism. Argentine torturers (trained in the U.S.) boasted to Father Rice in 1976, “Now you’ll find out that the Romans were very civilized towards the early Christians compared with what’s going to happen to you.”[i] In her heart-rending Cry of the People Penny Lernoux documents the suffering, arrest, torture and death of 850 priests, nuns and bishops. Not to speak of the massacre and immiseration of countless civilians. The advent of the “theology of Liberation” in the late 1960s created space for the idea of revolutionaries, preferably of course unarmed, defending Christian ideals, the poor and oppressed, and demanding social change. The German-Dutch poster of 1969-70 showing a smiling model dressed in nun’s habit tearing it open to reveal a Che tattoo (or paint-on) was more than a joke: it was about the church opening itself up to social justice.[ii]

All this is true even of Cuba, one of the least Catholic of Latin American countries. It was observed, under the heading “Papal trip to Cuba threatened by St Che,” that “Cuban state iconography even cultivates unstated comparisons with Christianity. While Castro is portrayed as an omniscient father figure, rarely seen but always present, Che is the adopted son … who made the ultimate sacrifice.”[iii] The Pope’s visit opened up new avenues and restored old privileges for the Catholic church in Cuba, where a prominent theologian such as Sergio Arce Martínez could write a book testifying to the coincidence of socialist Revolution and Christianity in that country.[iv]

Neither Fidel Castro nor Che Guevara, nor any Cuban revolutionary leader advertised their atheism; indeed both showed respect for revolutionary Christians, who can now be members of the Cuban Communist Party. On entering Havana in 1959, Fidel wore a Christian cross round his neck, a gift from a child. He has said that Christ was a great revolutionary, and was always eager to address and converse with Christian clergy and laity.[v] Che himself showed some knowledge of the gospels and used religious language, asking, for instance, to be “baptized” at the river “Jordan” in Bolivia, and applying religious symbolism to his description of the travails of the peasantry. It is little known fact, which I get from a work significantly titled Il Che: l’amore, la politica, la rivolta, that on 25 May 1964 Che, together with his relatives, received a papal plenary indulgence of all his sins, thanks to a pious aunt.[vi]

Although some, like Peter Weiss, have seen Che as substitute for Jesus in a non-believing age, it may be more rational to see him as an accretion, or tributary, or renewal of Christ, a secular Jesus or secular saint of which there have been many in history, like Gandhi, Martin Luther King, or Nelson Mandela (himself, like Che, reviled by the U.S. government as a terrorist), for instance. But the Che-Jesus fusion is to a degree literal. It is on the Internet, which under “Chesucristo” serves up first this unambiguous picture (FIG 1).

“The true revolutionary is guided by feelings of great love.” This phrase is now taken to encapsulate Guevarian social philosophy. It appears not only on many posters, but also at the entrance to the museum of the command post of Che on the Fortress of Havana, where, ironically, he presided over the trials and execution of Batista criminals. It informed not only his daily life – his well-documented affection for family, friends and animals – but also his guerrilla strategy, where he was merciful to enemy combatants to a degree that may be unique in military history. He was always concerned to treat the enemy wounded as well as his own, even to the last, when captured and wounded himself. His humanitarianism, his concern for the wounded and to minimize deaths may have been a military disadvantage; and he describes in his Bolivian Diary (3 June 1967) how he could not bring himself to shoot at some soldiers sleeping peacefully in the back of a truck, letting them pass unscathed. A collection of essays by and about Che compiled to demonstrate his humour and humanity is entitled La tentación de un beso, referring to the kiss he wanted but feared to place on the forehead of a dying comrade, which he might interpret as the kiss of death.[vii]

Christ is always represented as perfect love and compassion, although he must have been angry not just at the moneychangers in the temple, but at the cruelty, injustice and stupidity he saw around him. A revolutionary such as Che was fuelled by both anger and love. Marxism is not generally viewed as a philosophy of love, but we find Che quoting Fidel “It was precisely love for man which conceived Marxism, it was love for man, humanity, the desire to combat misery, injustice and all exploitation.”[viii] Art and particularly poetry speak of Che virtually as a lover, in the most intimate fashion; to cite just the most famous song or “hymn” with words by Cuban laureate Nicolas Guillén and music by Carlos Puebla: “here lingers the bright, precious transparency of your beloved presence, comandante Che Guevara.” He is also Nature, Cosmos: water, wind, earth, sun and star. This is the stuff of countless religious poems; and there have been a hundred love-poems to Che.[ix] The immense photographic record of Che is, in general, that of a loving, smiling, happy, genial man. This was not just a pose for the press as it is with our politicians, from this press-shy man. Che has become a primary advocate of peace, social justice, and humanitarianism, the embodiment of noble sacrifice, selflessness, and the egalitarian striving of social democracy if not of socialism itself.

To all these ideals, which are all theoretically Christian, one photograph of Che Guevara, of the thousands that exist, has maintained itself through the years since his death: that taken by the Cuban photographer Korda. It has been called the most reproduced and adapted photograph of the century, the Mona Lisa of photography, recurring in countless posters, T shirts and artifacts.[x] It has become as the guiding star in a constellation of comparable photographs, the Che of a shining vision transcending the idea of “mere” armed struggle.

It was not always so. The change is significant. My first visit to Cuba in 1973 coincided with the 20th anniversary of Fidel’s Attack on the Moncada barracks, that is, the first armed action again Batista, and the destruction of Allende in Chile. There were guns on the posters everywhere, and the U.S.-abetted “other 9/ll” which drowned Chile’s road to socialism in blood seemed to prove that it cannot be peaceful, that without guns to defend the new principles, they are doomed. But by the 1980s those guns were fast disappearing in the revolutionary iconography, as Cuba foreswore aid to popular struggles (except in Angola). The OSPAAAL (Third World Solidarity) posters supporting those struggles emphasized human rights, and victimhood, rather the erstwhile necessary counter-violence. Guns are now those of the oppressor, and billboards in Havana now carry bland “peace and justice” slogans.

The idea of revolution began literally to smile and sweeten, to become poetic and aesthetic, a serene vision of the future rather than the anguished imperative of the present. To this process Korda’s famous photograph of Che was perfectly adapted. Although Korda himself continued in interviews to remind us of the cold, “blind” ferocious anger that he knew Che must have been feeling at the moment he was snapped, that he, Korda was also feeling at the time, at a commemoration ceremony for the victims of the sabotage (probably U.S. -abetted), of a ship in Havana harbor, killing over a hundred, a “pain and anger” that he thought he had captured in the face, the expression immortalized in the photograph was more widely interpreted as that of the serene visionary, a Christ-like soaring of pure spirit beyond mere human suffering. As Pierre Kalfon noted “this image of a man in a cold rage will become the icon of the revolutionary with the face of an archangel, sweet, almost mystical.”[xi]

If Korda’s photo has become part of a consensus towards the pacification of Che, is this consensus in recognition of so many defeats, a surrender of the left, a perceived failure of socialism? Does he then survive only as a harmless T shirt icon? The big media, many Che biographers and a recent exhibition[xii] have stressed the kitschification of Che, the big media with glee, most of us with misgivings or mixed feelings at the very least. The corporate world, adept at co-optation, would have us think that the once fearsome revolutionary has been reduced to a pretty meaningless symbol. Rather, I would say the “real” Che has not died, but undergone a tactical shift, and one can believe, with Ariel Dorfman, that “deep inside that T shirt where we have tried to trap him, the eyes of Che Guevara are still burning with impatience.”[xiii] No doubt that the once fierce revolutionary has become “Man, companion, friend”, in the title of a book, poster and video-cassette by Italian Che Guevara Society president Roberto Massari, showing Che in bed, smiling broadly, cradling a puppy in his arms.[xiv] It is often said (by Jon Lee Anderson among others) that Che would roll over in his grave at the sight of all those “meaningless” Che T shirts. My own feeling is that Che would have those T-shirt wearers imagine themselves being stopped by him in the street and asked: You bear my image. What are you doing about it?

Some obvious visual pointers, tending clearly to the demilitarization of Che: the Korda photograph is one of the very few where Che is not wearing the military uniform otherwise his invariable public garb. He wears instead a dark green leather or vinyl jacket, lined in navy blue, which a friend bought for him in Mexico. The beret is generally associated more with the intellectual than the military or guerrilla (despite the “Green Berets”), the guerrilleros preferring the peaked cap, which is obviously more convenient for taking on and off, and for giving shade. The long hair, shaking calligraphically in the wind, as it were his ideas flying off into space (as has been said), is definitely non- or anti-military, anti-corporate, Sixties-hippie, and distinguishes this photo from the second favourite, by René Burri, where Che’s hair is short, and where moreover, he is smoking a cigar, as he does, holding it in mouth or hand, in so many photographs. The absence of evidence for Che’s cigar addiction makes Che look less Cuban but more acceptable to the current, world-wide drift which sees smoking as foolish and suicidal, rather than glamorous – not to speak of redolent of enslavement to the big, murderous corporation. Jesus didn’t smoke. Even Fidel gave up smoking, for his health and to set an example. There are posters of Che based on photographs where the cigar is removed.

The resemblance to aspects of Christ’s life on earth can be easily traced in the life of Che. Both died young, in their thirties. Both were doctors – Christ as miracle healer, Che as the trained physician, active as such even or especially when he was fighting, doctoring when others were resting, or escaping. Both men were particularly concerned with leprosy, the disease of the downtrodden and outcast, as The Motorcycle Diaries (books and film) have reminded us in the case of Che. Like Che Jesus was an egalitarian, a communist in terms of bidding his disciples to hold all in common, and generally spurn material comforts and possession. Both were strict disciplinarians, who insisted on individuals leaving families, friends and privileges behind to join him, sacrificing all and if need be, their own lives. Said a comrade of Che “He was superstrict, like Jesus Christ.”[xv] The physical sufferings in his life, if not death, seem to have exceeded those recorded of Christ, who was not afflicted (as far as we know) with any disease such as Che’s asthma, and fasted voluntarily, whereas Che and his men were is constant danger of painful wounds, starvation, laceration by stones and thorny bushes, and drowning in rivers. Death accompanied by the most horrible tortures awaited them if captured. Che’s leaving Cuba and prestigious roles in government for the solitudes, discomforts and martyrdom in the jungle represent an active rejection of material comforts such as was enjoined upon the apostles. It is fitting, somehow, that one of the two most popular, and ecumenical images of Christ of the 20th century, Heinrich Hofmann’s painting of 1889, shows Jesus looking slightly down, at the Rich Young Man who is told he must give up his wealth and comforts if he wants to join him.[xvi] The rich young man is invariably excluded from this Jesus, who is cropped from the larger picture to bust-portrait format, symbolically one might say, in view of the historic attachment of the Christian Churches to their immense wealth and comforts.

Hoffmann’s, and his only real “rival” in popularity, the Jesus of Werner Sallman, succeeded because of their perfect blend of masculinity and femininity. This is true also of Korda’s photograph. The term “beauty” is used for the face, (feminine) hair and beard of Che, “not just handsome, but beautiful” (I.F. Stone), without undermining our sense of a perfect masculinity. Indeed, it is this feminine-masculine fusion, possessed by some film actors, which adds to our sense of Che’s being the “complete human being” of his age, as Sartre said. The “new man” represented by Che was also a new bi-gendered person.

In some respects, Jesus was treated better than Che. He got a trial, or a form of a trial. His body, after execution, was taken down and left to the care of his loved ones to mourn and inter; Che’s after exhibition to public shame was desecrated (the hands amputated) then hidden. Like Jesus’ his body disappeared, Che’s for thirty years. Not even his own brother, with legal rights to its disposal, was allowed to see it, much less take possession of it. And as with Jesus, there were some who could not believe he was really dead.

CHESUCRISTO IN ART: a shared symbology

“Hoy hay que impedirte de ser Dios” (Now we have to prevent you from being God, graffito on ceiling beam in laundry room of Vallegrande hospital where the dead Che was exposed.)

It is nothing new for the long-suffering Latin Americans to identify with the sufferings of Christ, and see themselves as Christ-like socio-political victims. In 1932 Siqueiros painted in Los Angeles an America Tropical showing an Indian crucified under the spreading wings of a bird of prey. A Cuban poster by Rafael Enríquez c. 1980 shows the Latin American campesino bound to the cross of Foreign Debt and the International Monetary Fund.[xvii] The Crucifixion of Central America or the Triumph of Neo-Liberalism is the title given to the crucified Christ painted by the Italo-Nicaraguan painter Sergio Michilini in the spiritual retreat center near Managua named after Oscar Arnulfo Romero, the Salvadoran archbishop murdered by U.S. -trained and -funded death squads while saying mass.[xviii] The suffering Christ was the dominant popular, but not the only type: witness the exceptional Christ guerrillero already referred to, conspicuously armed with a rifle, of the Rostgaard poster (FIG 2), banned from exhibitions of Cuban posters in Catholic countries, and the Che-Christ, arms stretched out on the cross of his gun over the inscription Ecce Homo, in a painting by Frenchman Lionel Ducos (FIG 3). Otherwise the Che-Christ fusion has been in keeping with a general pacification of the Che image, where the gun has been replaced by other (or no) symbols, and the association is with doves and other symbols of peace. Che was of course no pacifist (was the Jesus who drove the money-changers from the Temple, in an attempted coup against the Romans?). The underlying idea here is that there can be no peace without Justice: and Che stands, now, above all for social justice, and the necessity of sacrifice: Che, like the suffering Christ, was a sacrifice to the prevailing ideology.

The Cuban revolutionaries were on the whole not Christians, but one quasi-Cuban hero-martyr was: Camilo Torres, Colombian Catholic priest who died in battle in Colombia 1966. In a book called Che Guevara seen by a Christian, the ethical significance of his revolutionary choice, by the Italian theologian of liberation Giulio Girardi, Camilo is quoted as saying in effect, I am not a revolutionary rather than a priest, but because I am a priest.[xix] Of the several Cuban posters celebrating his sacrifice, one (from OCLAE) shows the Christian cross turned with one arm into a gun, another shows Torres’ gun hung with crucifixes. But these are early, in tune with the prevalent gun imagery in Cuban poster art in the early period from the ‘60s through the early 1970s. The guns disappeared, along with Cuba’s overt support for armed struggle in the Third World. Cuba was not even much involved in the armed making or defence of the Nicaraguan Revolution, with which it heartily sympathized, and in which Christianity and Christians played a major role. “Who can doubt that on the day of justice, when he judges with these standards [i.e. identification with the poor, hungry and imprisoned], Christ will recognize Che Guevara, Carlos Fonseca …[and other Nicaraguan martyrs].”[xx]

It is significant that scarcely a single image in the huge Imagen Constante exhibition held in Havana in August 1997, into which Che designs poured by the hundred from all over the world, shows the revolutionary bearing a gun, or associated with armed struggle. A conspicuous exception was a design from North Korea, the gun in Che’s hand thrust towards us, the Korda face seeming quietly defiant in this context. By this time Che-related murals featured him with doves of peace and flowers rather than military hardware. Mun~oz Bachs shows Che with flowers, and angelic wings; in an Alicia Leal painting, a resurrected Che sits quietly with a Cuban family surrounded by exotic birds, and elsewhere, by the same artist, explores a luxurious paradise of flora and fauna, like Adam.

We may take in turn the classically reiterated Christian symbols, especially those related to the Passion, as applied to Che, before assessing how he physically substitutes for Christ in the pivotal moments of the Passion: Last Supper, Crucifixion, Deposition/Pietá, and Resurrection.

CHE/IHS To start with the name: the trio of letters comprising Che’s nickname is in art of all kinds an icon in itself, sacred symbol, pathway, invocation, even sculptural monument, akin to that of Jesus, whose holy name was codified into three letters (IHS, first three letters of the name in Greek, and acronym from the Latin Jesus Savior of Man) and iconicized especially by the Jesuits in 16th to 17th century art.

The star. The star is a universal, cross-cultural symbol of light, spirit, destiny, guidance, mission, wisdom, transcendence, immortality. Che is identified with all of these grand concepts, especially in relatively unchristian Cuba, where directly Christian symbolism is absent from official imagery. In the Christian story the star is first of all that which guided the Wise Men to the infant Jesus, and guides us to him and our destiny still. With Che the star starts as a small material object, the insignia of comandante vouchsafed to him by Fidel, in a touching, well-known incident from the Sierra Maestra guerrilla war period, when he was invited by Fidel to add the cherished, rarely given title to his signature on a letter of condolence. Che wore that star, the only insignia of his rank, proudly in his beret ever since. A modest twinkle in the Korda photo, the star shoots from that point in dazzling metaphorical trajectories in the posters. The polychrome, luminous radiation from the star suffuses the whole body from its birth in the beret of Rostgaard’s (Korda) Che (FIG 4), reminiscent in its way of a conventional Christ-image, where the light is made to emanate from Jesus’ figure, and wounds in various ways.

In a Raúl Martínez design stars of thought, emblems of stellar ideas rise in increasing magnitude to encompass the globe (FIG 5), the same artist has them studding a dense, jungle-like growth of hair and beard. The star explodes into fiery furnace of light in a mural by students of Walter Solón Romero in the University of San Andrés in La Paz, Bolivia (FIG 6). It burned literally in metres-high flames in the huge (Korda) face made of flipped boards by people attending the closing ceremonies of the Youth Festival, Havana August 1997. In Jorge Fernández’ Che de América poster, the whole head and face is formed by stars.

Abstracted from the face and other physical context, the star stands, with the Korda face cut out of the center, on a monumental scale and in highly polished aluminum, waxing and waning or refracted in time and perspective, in nine repetitions in the courtyard of the Palacio de los Pioneros , Parque Lenin, near Havana (FIG 7). Abstracted further still, rendered in a critical light, it hides behind a barrier of Tropicola cans, in a design called Hecho Historia Sra, Hecho Historia (by Osmany Torres) which won second prize at the Imagen Constante exhibition. Over it is written large “Donde Estas, Caballero Gallardo,” the same phrase used for the star placed out of reach in a plain black firmament. This is the Cuban and a typical worry for all who respect the man: Ubiquitous, but unreachable, an admirable but impossible ideal, even in Cuba Che risks becoming a banal symbol of no substance, with less brand recognition than the next soft drink.

The halo, saint. The halo sanctifies, in the first instance, before it christifies. On the Spiegel cover (FIG 8) which imagines Che grown old and careworn, the halo is with deliberate, discreet ambiguity studded with bullets; in the T-shirt version these bullets are further elided to resemble decoration. A series of wood sculptures called En el Mar de America by Alejandro Aguilera[xxi] shows a file of crudely worked “saints”: Bartolomé de las Casas, Don Quixote, Bolívar, José Martí and Che, all haloed. In the reverse process, Jesus’ halo is replaced by Che’s starred beret, while a third of Che’s face looms behind and over the conventional face of Jesus, in a collage by Michael Dickinson, for his play The Rich Young Man, a respectfully materialist interpretation of the Passion. In other Cuban works he is a tutelary saint (La Pasión de Ernesto, painting by Ernesto Rancan~o), a St George with the dragon (Un soldado de América, painting by Alicia Leal), and Adam wandering in Paradise with the animals by the same artist. Like saints on the wings of altarpieces, he is simply present, a witness, for Christ in Cuban folk art, and notably, in an ecclesiastical mural in Nicaragua, as the fascinated observer, accompanied by hero-martyrs Sandino, Carlos Fonseca and Archbishop Romero, at the birth of Christ (FIG 9).[xxii]

Crown of Thorns A profile of Che with a crown of thorn-like stars was exhibited by Cuban Roberto Fábulo Pérez in Havana 1997. From Bolivia, Vallegrandino Oscar Rojas gives him in a pyrographic portrait based on a photo of the dead Che, a crown of barbed wire (FIG 10). A Tee shirt design bisects the face of Che, identifiable by the star in the beret, with that of Christ, identifiable by the crown of thorns (to the words Es justo ser revolucionario). The cover of the Pedro Esteban~ez’ Palabra de Che Guevara shows a soft-focus version of the Korda Che, sad, haloed with light all round the head, and the crown of thorns across the brow (FIG 11). Note the use of the word “palabra” to evoke the sacred “word” of Christ.

Stigmata Two examples: the star functioning as stigma over a handprint on a poster called Estigma Guerrillera, and, very curiously, from Catholic Bolivia, Che’s face peering, narrow-eyed, from a Tee shirt worn behind what appears to be an open jeans jacket, at the neck of which there hang the CND Peace symbol and a finely crafted crucifixion pendant. A slit on the right of the jacket pretends to function as a buttonhole, but it is clearly too long and the prominent, excessive stitching around it suggests bleeding (FIG 12). This must be the chest-wound of Christ, an object of virtually sexual veneration in German baroque, and no doubt other mystical poetry.

The Last Supper In a student dormitory of Stanford, California, after a poll among students and workers, Che was chosen to replace the eucharistic Christ at the Last Supper, surrounded by Chicano heroes (FIG 13).[xxiii] The cover of Juan Ignacio Siles del Valle’s La Guerrilla del Che y la narrativa boliviana (1996?) uses a preliminary drawing for Leonardo’s famous Last Supper as a comparison with a photograph of the Bolivian guerrillas around a camp fire.

Crucifixion The Christian crucifix, as a standard neck ornament, hangs next to a necklace emblazoned with a miniaturized version of the Korda Che, in the market of Santa Cruz, Bolivia, just as the straight portrait of Che hangs next to that of Christ in a Cuban home.[xxiv] These are “mere” juxtapositions, suggesting that Che reaches a comparable, or shared level of devotion; or that Jesus himself, by his propinquity, validates the sanctity of a successor. This is the message, indeed, and more, of Carlos Salazar from Vallegrande, in a low relief exhibition sculpture exhibited in 1997 in that town, where from his Cross, Jesus gazes, hanging in pain on the cross, down upon another martyr (not just to his, but also His cause? – FIG 14). In Pierre Kalfon’s film El Che, the schoolmistress Julia Cortez, the only civilian to talk to the captured Che, is interviewed as saying that when she re-entered the schoolhouse after hearing the shots that killed him, she found him lying on his back “his arms stretched out in a cross.” In Bolivia, where Catholic imagery is more to be expected than in Cuba, we find in Walter Solón Romero’s El Cristo de la Higuera, a large mural in the Centro Médico in La Paz, Che embracing and entwined with a fig tree (referring to La Higuera where Che was executed, but also the “tree” of the Cross), from which he looks down at a medical operation and the artist’s family, including a son who was imprisoned and tortured by the Bolivian military after Che’s death.

From Argentina we have a remarkable transfusion of the very face of Christ into that of Che, via the veil of Veronica which is imprinted with the face of the (dead) guerrilla , taken from a photograph of him on his bier (FIG 15). The Christ who looks down upon his image thus transformed combines, in a dismembered form, his moment upon the cross with the moment when, according to legend, he stumbled under the weight of it, and St Veronica (the name means “true image”) pressed her veil upon his face to dry the sweat and receive, miraculously, the holy image. (This cloth, in which the corpse of Jesus was also legendarily wrapped, is believed by many to have survived, under the name of the shroud of Turin).

But for the naked truth about Nicaraguan feelings for Che, as that little country tried to build a revolution in which many priests and Christian layfolk participated, we turn to a small “primitivist” painting (also posterized) by Raúl Arellano, where a totally naked, and very well-endowed Christ stands crucified under a label “Subversivo” (FIG 16). He wears unmistakably Che’s beret and facial hair, and the peasants praying to him are invested with equally contemporary identification as Nicaraguan peasant women, while Somoza’s national guardsmen attack him from the other side. This both re-historicizes and politicizes the gospel in a manner not unusual in Nicaragua at that time. About 1984 I heard Padre Uriel Molina, in his church of Santa Maria de los Angeles located in the poor Riguero barrio of Managua, which he had had decorated with a blend of traditional Christian and Sandinista saints, re-interpret the parable of the Good Samaritan in a Sandinista, anti-US. imperialist light.

This is straightforward. At an extreme end of “modernist” interpretive complexity and peculiarity lies the Corpus (1996) of Spanish artist Rogelio Lopéz Cuenca, who arranges the face of Che (dead), the mutilated body of Warhol, apotropaic (fatma) hands and the wounded feet (one of Che? The other of an astronaut), all in Christian cross formation.[xxv] A Che-and-crucifixion which also presents a particular interpretive challenge is the Che with the Yellow Christ, by Sergio Michilini, where the face of Che (not, for once, Korda’s) substitutes for that of Gauguin in his Self-Portrait with Yellow Christ, of c. 1890. The crucified Christ has the yellow of Gauguin’s original (a Breton medieval sculpture), but the attitude of Michilini’s own Crucifixion as painted in the Oscar Arnulfo Romero Spiritual Center near Managua, Nicaragua (FIG 17). The relationship: Michilini–Gauguin-Christ triangulates between atheism, art and Christianity.[xxvi]

A verbal graphic called Nails as Bullets[xxvii] in honor of Che and Néstor Paz Zamora, a Christian mystic and guerrillero of Bolivia, is thus configured:

CLAVOS COMO BALAS

Néstor

Clavados los ví en la guerrilla

ernesto

erchesto

ercresto

ercristo

el cristo

Christ in death; Deposition/Pietá “He was like a Christ taken down from the Cross …” (Peter Weiss).[xxviii]

“Then we saw the incredible photo: the eyes were half open between death and life, defenceless like a convalescent… I remembered one of those Descents glimpsed in some forgotten painting, Christ taken down from the cross, supported by the pious women. The same lunar pallor of death, the same stripping of clothes from the man left bare-chested…”[xxix]

Che’s body, naked from the waist up, bullet-ridden but cleaned up, eyes open, was exhibited by the Bolivian military for a couple of days in Vallegrande in the little laundry room of the local hospital. Intended simply to prove that this was indeed Che, marked by bullet holes supposedly received in combat (soon proved a lie), the sight inspired in the locals the feeling that they were in the presence of a living Christ about to resurrect. The nuns who washed the body and the doctors who treated it had a similar feelings, which was corroborated around the world when the photographs were published. These photographs of the dead Che, the best of them by Bolivian Freddy Alborta (FIG 18), set the stage for the christification which was soon to be consummated by Korda’s of the living Che.

The English art critic and novelist John Berger was the first to note the similarity between this Alborta photograph, the best known of all, and Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp (1632). Later, comparisons were made with the foreshortened Deposition by Mantegna and Holbein’s Christ in the Tomb, where Christ is unusually emaciated, human, and frightening. In the early 1970s the Mexican artist Belkin took up the comparison with Rembrandt’s famous painting, in four curious and philosophically complex variations, in the last of which, called The Final Anatomy Lesson (FIG 19), Che (previously cast in the series as the criminal being anatomised) becomes Dr Tulp, appearing to lecture to us and the guerrilleros from the Bolivian campaign who substitute for the surgeons, on the robotic anatomy of imperialism (or: on the anatomy of a robotic imperialism).[xxx] In Rembrandt’s painting, Dr Tulp has been seen as a kind of Christ-figure teaching disciples about human evil (represented in the corpse, necessarily that of a really bad criminal); while the Bolivian officers’ pointing to the bullet-holes in Che’s chest is compared to the ostentatio vulnerum, the demonstration of Christ’s wounds, or a Doubting Thomas poking his finger in the side of the Resurrected Christ. A reproduction of one of the dead Che photographs, in Ramparts March 5 1968, was deemed by a historian close to the U.S. State Department, as “remarkably Christ-like,” “a contemporary Pietà.”[xxxi]

The stricken face of Che, in the last photograph of him taken alive, has been compared to an Ecce Homo, and a photograph of his head, post-mortem, has served, as we have seen, the Argentine Castagnino (FIG 15), as the Alborta of the whole extended and foreshortened body did the Bolivian Salazar (FIG 14). The conjunction, from a citizen living in the town dedicated to shrines of Che, where he is honored even by the local Catholic priest, could not be more apt. In La Higuera the latest, thrice life-size bust of Che was erected (1997) next to a rock bearing a large crucifix.

Resurrection. In 1897 the illustrious Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler painted Wilhelm Tell in an image (in Solothurn) which has become the iconic version of the founder of the Swiss nation, reproduced, for instance, on a Swiss postage stamp. The pose was based on that of a classic Christ resurrecting, and blessing with one hand, the other grasping a flag with the red cross of salvation, replaced by Hodler with a crossbow. A much simplified, Michelangelesque version by Swiss designer Richard Frick (also author of a fine compilation of Cuban OSPAAAL posters), to celebrate a Mayday event 2005, substitutes the Korda Che head, and adapts the crossbow into that used to authenticate Swiss-made products – here, a blessing upon the world. The lifting into the skies and transfer by helicopter of Che’s corpse from La Higuera to Vallegrande has also been seen as a kind of resurrection.

Miracles. The Bolivians were very sad and angry that Che’s bones, finally unearthed after being hidden for thirty years, were removed in 1997 to Cuba, calling it “grave-robbing.” They were deprived of sacred relics. Miracles of various kinds – animals healed and found, people cured and transformed, nature influenced, prayers answered – have been reported from La Higuera and Vallegrande. The local priest in Vallegrande (La Higuera has none) found himself obliged to render up prayers for Che, virtually pray “to him.” For a young fatherless boy in La Higuera, the “miracle” was the “paternal” incentive to study hard he received from the spirit and images of Che which he kept in and painted on his house.[xxxii] On the other hand, Catholic credulity about miracles is tested and mocked in a photographic installation by the Catalan artist Joan Fontecuberta. His Miracles and Co. installation featured a “Miracle of the Flesh” (FIG 20), which may be practiced with a leg of ham (corned beef for the Muslim novice is not effective) that when sliced finely, reveals “the face of Che Guevara, which some have confused with that of Jesus Christ.” (In other circumstances, the face of Hitler, and more rarely, Bin Laden may appear).[xxxiii]

Film and video. Richard Dindo’s Bolivian Diaries reconstructs Che’s last campaign as a poetic reverie on willed death and destiny, in which at one point, resting in a peasant hut, Che contemplates firewood burning in the shape of a cross. Roger Spottiswoode’s Under Fire (1983) makes a dramatic and moral pivot out of the moment when the film’s protagonist, a professional photographer, is asked by Nicaraguan guerrilleros to take a picture of their hero (modeled on real-life revolutionary Carlos Fonseca), who has just been killed in combat, faking it to make him look alive. This is to be done on the assumption that documentary proof of the survival of the revolutionary will prevent the U.S. from sending more arms to Somoza. The idea, and the photograph itself are clearly based on the (Alborta) pictures of the dead “Christ-like” Che.

Religious feeling in general ranges on a scale between intimacy and inaccessibility. So too the reaction to the idea of Che. The intention of José Toirac, a younger Cuban artist, of a generation that feels chronologically distanced from Che, was to create out of the recumbent, dead flesh a sense of intense physical proximity infused with meditative mystery. His Requiem video (exhibited in Havana 2005) slows down and turns into an endless loop, back and forth, from head to toe, using a fragment of black and white moving film made of the dead Che. In its original 16mm film form only a few seconds long, it stretches into a precisely measured meditation over a minute long each way, passing from the silent staring face, via the bruised and penetrated rib, the formlessly wrinkled trouser, to the lacerated ankle, and back again with neither end nor beginning, The very low pulsing sound in the background hollows the space, and further slows the pace.

Toirac’s Reliquias que nunca vimos (Relics we never saw) is an installation featuring casts of a face and cut-off hands imagined as those of Che, the “mythic Delegate or Son of God.” Toirac’s Hecho en Manila (1998) uses Che’s Bolivian Diaries as the starting point for evocation of the Last Supper and Holy Eucharist, with its thirteen plates each imprinted with a photograph of the dead Che, “the body of the hero offered for food.”[xxxiv] El Alma, El Cuerpo, Transubstanción, is a three-part installation, extrapolating from the Bolivian campaign into the Passion: the track leading to the hut of Honorato Rojas, who betrayed Che, evokes Judas; the helicopter journey that took Che’s corpse from La Higuera to Vallegrande suggests the Ascension, and the laundry sink of the hospital there the empty tomb; the finger of the officer pointing to the bullet wound in Che’s chest evokes the Incredulity of St Thomas. “Sacrifice”, drawings recently exhibited in Austin, Texas, is explicitly eucharistic: the sacramental “this is my blood, which is shed for you” is illustrated by drawings delineated and washed in red wine, dried to brown shades of blood, the brush as it were “dipped in an open vein” of a man living in the shadow of death (Jesus-Che) and facing the ultimate sacrifice; also displayed is the Holy Sheet (of St Veronica). The absorption of Che with the Jesus of Passion and Eucharist is linked to the artist’s homeland.[xxxv]

All this surprises more in a Cuban than a Bolivian; yet it is a Cuban again, journalist Pablo Guadarrama G., whose intention in visiting the site of “San Ernesto de la Higuera” was to “discover the stations of the calvary of that heretic martyr and heretic of religions and philosophies” corresponding to the “new kind of new image of Christ crucified.”[xxxvi] Another, avowedly Christian Latin American visitor to the sacred sites in Bolivia, writing under the heading The Gospel of Che, felt he had encountered a new chapter in the history of salvation, written according to the “new and perennial Gospel of Che Guevara.” “For the people there will never be a stone that closes his tomb, that separates death from life.”[xxxvii]

Finally, Argentinian-American Leandro Katz 16 mm film El Día que me quieras (The day that you’ll love me, 1998) keeps the image of the slain Guevara at the center throughout, as the “Christ-like martyr of international liberation struggles,” and in accord with the confession of Alborta, interviewed at length in the film, “I had the impression I was photographing Christ.”[xxxviii] The extreme croppings and close-ups feel like the fumblings of a scholar trying to make sense of variant and contradictory gospel narratives. Then, suddenly, we realise that Che’s is not the only body there: in a wide-angle shot of the room we see revealed the hideously disfigured corpses of other slain guerrillas, who had not undergone the cleaning up process like Guevara. It is as if we suddenly became aware, in some Northern Renaissance crucifixion painting, that Christ’s perfect body in the traditional dignified pose is flanked by horribly distorted figures of the thieves, writhing in agony upon their crosses, to indicate that they do not accept their suffering, and Salvation, as does Jesus – but might be innocent as Jesus.

RESURRECTION 2: The Anglican Che-Christ There have been many other artistic applications of the Che-Christ fusion; I list some of them elsewhere.[xxxix] We end on the most remarkable very public and semi-institutional use of the fusion, which reverses the process we have been considering: not so much Che into Christ as Christ into Che. This occurred in a campaign devised by the Churches Advertising Network (CAN), founded in Britain 1991, which calls itself an “independent ecumenical group of Christian communicators,”[xl] working with a group of about thirty professional ad-people calling themselves Christians in Media. But in this case it was Anglicans (and Methodists) who took responsibility for the controversial fusion, to the alarm of prominent Catholics, and silence from the (Anglican) Archbishop of Canterbury. The campaign was mounted at a time of a perceived continuing decline in (Protestant, Anglican) church attendance, which had even fallen behind that of British Muslims in mosques.

Previous efforts of CAN showed imagination and humour. There was a poster enlarging a fake small ad. for “BETHLEHEM. One star accomodation. Self-catering only. Animals welcome. Cot provided,” and a cartoon of three ribald, punkish kings saluting the (invisible) holy family, over the words “Bad hair day?! You’re a virgin, you’ve just given birth and now three kings have shown up,” which was banned in a number of Anglican dioceses and created a minor furore in the press. There was worse to come.

In the beginning of 1999 what became known as the “Discover the Real Jesus” and alternatively the “Che Guevara” poster was produced in five different sizes, ranging from stickers and postcards to five foot by three, suitable to hanging in train stations, bus shelters and, multiplied, on standard billboards – at least eighty of the latter around the country (FIG 21). For the press, the reaction made for uproarious copy, with repercussions in Europe and the U.S. Newspaper headlines were in no doubt that the “CHURCH POSTER SHOWS JESUS AS [not “like”!] CHE GUEVARA.”[xli] It was officially denounced by the Catholic church. One M.P. called it “grossly sacrilegious.”[xlii] Dr William Beaver, spokesperson and Communications Director of the Church of England, denounced it utterly as in “no way, shape or form” appropriate. A Daily Mail editorial was in “despair” over the promotion of “such offensive, dishonest and ignorant rubbish.”[xliii] To associate Jesus with Che was to “trivialize the mystery of the godhead,” said the Bishop of Wakefield,[xliv] as if association with the most universally accepted of 20th century revolutionaries was “trivialization.” Predictably, objections were raised that Jesus was not a political revolutionary. But Robert Griffith, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, liked the poster: “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Che Guevara fought against poverty and oppression. It is encouraging to see the churches pay tribute to an outstanding Communist,” and the Daily Mail (Feb. 10) was moved to headline its Letters page, summarizing a letter from California, with “Che was sacrificed for peace, just like Jesus.” The Salvation Army was particularly enthusiastic, splashing the image on the front page of its journal The War Cry. A Socialist Party representative, on the other hand, sniffed “It’s all a bit unfair to Che Guevara.”

The broad idea was to counter the idea of Jesus-for-nursery-school stereotype, with the text below starting “Meek and Mild. As If.”[xlv] (The reference is to a famous Charles Wesley children’s hymn which goes “gentle Jesus meek and mild”…) The “official” line of the Churches Advertising Network and the clergy involved was given by the Rev. Tom Ambrose, then communications director of the Ely diocese: “Jesus is not a meek, mild wimp in a nightie, but a real, strong, passionate, caring person … [who] was crucified exactly because he was a revolutionary.” The poster appeals to those who “respect” what Che Guevara was trying to do. Ambrose went to offer a curious “revolutionary” re-reading of the Feeding of the Five Thousand (already used by Fidel Castro as akin to the intentions of Cuban socialism): ‘it’s about 5,000 men hiding away in companies of 50 and 100, drawn up like an [guerrilla] army.” This appeared in a whole page of the Independent for Jan. 7 (Thursday Review), running a thoughtful article on “The Reverend Revolutionaries”: Ambrose and Rev. Peter Owen-Jones, an ex-advertising copywriter, whose portraits flank the Che poster in a similar high-contrast style. Ambrose’s personal view is that the campaign had an “immeasurable effect,” “the overwhelming response has been favourable … [with] surprisingly only two hate-mails, from America.”[xlvi]

The poster was given a significant art-world imprimatur by being included, as one of the very few 20th century images used, in a National Gallery, London exhibition (also in Glasgow), and its associated BBC program “Images of Salvation.” Achieving recognition throughout the English-speaking world and beyond, it has been called a “benchmark for church advertising in the U.K.”

Che was of course much in the air around this time, with the Pope’s visit to Cuba, the Korda lawsuit against Smirnoff,[xlvii] and the 40th anniversary of the Cuban revolution, in connection with which the Anglican poster appeared on TV, and in a BBC World Service segment as the warm-up to President Clinton’s State of the Union address. The Anglican Chesus was even picked up in Saudi Arabia, where the Christian media are not normally allowed.[xlviii] It just missed the feature broadcast on the BBC’s “Cuba Night” of Jan. 2, “Who Owns Che? The importance of NOT being Ernesto,” which was about commercialization, resemblance and visual copyright. Korda’s daughter Diana Diaz saw a reproduction of the poster while with the Alicia Alonso ballet company in the Dominican Republic, showed it to her father, who liked it, was flattered.

Emboldened by the success of the 1999 campaign, CAN came up with a comparable stunt for Christmas 2005, a perturbed (or just very serious) -looking infant in the same high contrast style, black and white against a red background. The text ran, in wall-stencil-like lettering: “Dec 25th. REVOLUTION / CELEBRATE THE BIRTH OF A HERO.” An earlier, seriously considered version of the design used an irregular, flattened halo embellished with one star in the center, thus reminiscent of Che’s beret, which was finally dropped (FIG 22). The working title was the “Che/Jesus” picture, and as such it was received. The campaign was, again, avowedly directed beyond regular churchgoers, and coupled with radio spots. The CAN website on the topic www.rejesus.co.uk and the related radio spots conducted a survey on attitudes, in which Jesus came out solidly as hero rather than zero, as black rather than white (!), as God rather than refugee, and (disturbingly) equally swear word and name and (even more disturbingly) as a bringer of war rather than peace (percentages all around two thirds to one third). Attitudes to Che were not polled (for good reason) but to the question posed “Why is it [the poster] modelled on Che Guevara?” the evasive answer came “that it was Jesus who was the real hero and revolutionary who changed the world, not Che.” Why then use the Che resemblance?? A more honest answer, in keeping with the campaign tactics as well as modern sensibilities, would have been to say, simply, that both were revolutionaries who in their different ways (and to different degrees), in vastly different historical circumstances, changed the world.[xlix]

Why did the poll show that a majority thought Jesus brought more war than peace – not the orthodox Christian view, of course, but one arguably borne out by history? I doubt that it was the British historical mind, never too much in evidence among the public at large, that determined this, but rather the perception, more wide-spread in Europe and especially in the Britain of Blair (a Catholic) than in the U.S., that Jesus has been co-opted by the war-mongering Right, that the Jesus of Bush and the Right is making a havoc of Afghanistan and Iraq, as he (He) has done all over the world when it came to fighting the supposed Left. Which should leave Che and Jesus squarely in opposition; but as we say, even as the Jesus of the Right has hardened, Che for the liberal/Left has softened. Catholic Latin America veers to the left. Che is a hero to the presidents of Bolivia and Venezuela. Is Chesucristo a way of taking the real Jesus –- revolutionary, egalitarian, friend of the poor-- back home again? end

[i] This segment draws on a longer piece called “Chesucristo” in David Kunzle, Icon Myth and Message, Fowler Museum, UCLA, 1997, p. 79, where more sources are given. For biblical history, I rely on Joel Carmichael, The Birth of Christianity, Reality and Myth, New York, Hippocrene, 1989. All posters referred are in the collection of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics, in Los Angeles.

[ii] Kunzle 1997 p. 95, fig. K.5, and Trisha Ziff, ed., Che Guevara: Revolutionary and Icon, Victoria and Albert Museum 2006, p. 102

[iii] Sunday Telegraph, 28 Dec. 1997, article by Philip Sherwell.

[iv] La Misión de la Iglesia en una sociedad Socialista. Un analisis teológico de la vocación de la iglesia cubana en el día de hoy, Editorial Caminos, Havana, 2004.

[v] See Fidel & Religion, Conversations with Frei Betto, Ocean Press, Melbourne 1990.

[vi] By Liliana Bucellini, Zelig, Milan, 1995, p. 15

[vii] Andrés Castillo Bernal, Che: La Tentación de un beso, Havana, Ed. Academia, 2000.

[viii] Rolando Bonachea and Nelson Valdes, Selected Writings of Che Guevara, M.I.T., 1969 p. 110

[ix] Bucellini p. 134

[x] For an incomparable array if the most disparate, Korda-Che derived imagery, see Ziff 2006 (cited n.2).

[xi] Pierre Kalfon, Che Ernesto Guevara, une légende du siècle, Seuil 1997, p. 286-287

[xii] Originally, at the Riverside, Ca., Museum of Photography, called Revolution and Commerce; the happier title at the Victoria and Albert Museum, opening 6 June 2006, was Che Guevara, Revolutionary and Icon. The exhibition is now traveling world-wide.

[xiii] Time, 14 June 1999, p. 212. See Ziff (cited n.2)

[xiv] Kunzle 1997, p. 84, fig 8.10.

[xv] Jon Lee Anderson, Che Guevara, A revolutionary Life, 1997, p. 504, quoting Orlando Borrego.

[xvi] See David Morgan, Visual Piety, 1998, and Colleen McDonnell, Material Christianity, 1995.

[xvii] Kunzle 1997, p. 79, fig. 8.2

[xviii] David Kunzle, The Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua 1979-1992, University of California, 1995, pp. 107-108, fig. 37b.

[xix] Che Guevara visto da un Cristiano. Il significato etico della su scelta rivoluzionaria, Sperling and Kupfer, Milano 2005 p. 259. My thanks to the author for sending me a copy of his book immediately upon publication

[xx] Giulio Girardi, Faith and Revolution in Nicaragua. Convergence and Contradictions, Orbius 1989, p.103.

[xxi] Repr. Luis Camnitzer, New Art of Cuba, 1994, p. 262

[xxii] Repr. David Kunzle, The Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua 1979-1992, 1992, col, pl. 18b.

[xxiii] Repr. Kunzle 1997 (see n.1), p. 87, fig. 8.17, with fuller description.

[xxiv] Repr. Kunzle 1997, p. 81 figs 8.5 and 8.6

[xxv] Kunzle 1997, p. 93 fig. J.4

[xxvi] See Kunzle 1997, p. 93, fig.J.4, and p. 85 fig. 8.13

[xxvii] Ramiro Barrenechea Zambrana ed., El Che en la Poesía Boliviana, La Paz, 1995, p. I “Nails as bullets. Nestor, I saw them nailed in the guerrilla …

[xxviii] Marianne Alexandre, Viva Che, London, 1968, p. 113.

[xxix] Fina García Marruz (Cuba), Para vivir como tu vives, Havana 1988 p. 62.

[xxx] For fuller analysis, and reproductions of all four paintings, see Kunzle 1997, p. 88 fig. 9.5.

[xxxi] Henry Butterfield Ryan, The Fall of Che Guevara, Oxford, 1998, p. 137.

[xxxii] Featured on the cover of Kunzle 1997.

[xxxiii] Press release for exhibition, held Jan-March 2003.

[xxxiv] Meira Marrero, “Ars Longa, Vita Brevis,” in Toirac, Mediaciones, Havana 2001, p. 11.

[xxxv] I take over the interpretation of Robert Fairey in The Austin Chronicle for Sep.5, 2003.

[xxxvi] Servando Serrano-Torrico ed., El Che despues de 28 an~os. Cochabamba, 1999, p. 18.

[xxxvii] Leo Wetli in Punto Final 25 Sep. 1997, no. 402, p. 25.

[xxxviii] See Jeffrrey Skoller, “The Future’s Past: Re-Imaging the Cuban Revolution, “ Afterimage 26, no.5, 13-15 March/April, 1999.

[xxxix] Kunzle 1997 (see n. 1), p. 91

[xl] Churches Advertising Network, Purpose and History, 2000. My thanks to Rev. Tom Ambrose for sending me this brochure, which carries the Jesus-Che image on the cover and other information. The same image is used on the cover of Selwyn Dawson’s Meet the Man. Jesus of Nazareth who became the Christ, 2000, and in Peter MacClaren’s Che Guevara, Paulo Freire and the Pedagogy of Revolution, with a comparison by the famous educational philosopher of Che and Jesus.

[xli] Daily Telegraph, Jan. 6 1999, p. 7

[xlii] Steve Doughty, “Blasphemy of church poster that compares Christ to Che,” Daily Mail, Jan. 6, 1999 p. 25. Cf also the Express Jan. 6 p. 21, and the Guardian Weekly Jan. 17, p. 29.

[xliii] Picked up by Los Angeles Times, Jan.7, 1999.

[xliv] The Independent Jan. 7.

[xlv] The words are taken from a well-known Victorian verses and hymn by Mrs Alexander: “Gentle Jesus, meek and mild/Look upon a little child / Pity my simplicitee / Suffer me to come to thee.”

[xlvi] Personal letter of 13 Feb. 1999.

[xlvii] For this, see Ziff (cited n.2) pp. 11, 21 and 26.

[xlviii] Interview with Tom Ambrose Sept. 2002

[xlix] The Religion correspondent of the Times in her report (14 Sep. 2005, p. 15) managed not to mention Che at all.